Inuit communities feeling the immediate effects of climate change

Climate change has cascading effects around the globe, within some of the most extreme environments marginalized communities are suffering due to changing climate patterns. The Inuit people have inhabited the hostile regions of the arctic for roughly five thousand years. Their nomadic areas of residence span four nations; Canada, Denmark, United States, and Russia. Within the territories of Canada the Inuit population numbers approximately sixty four thousand, with seventy five percent residing in Nunavut (Nuttall, 2007). Inuit people are dedicated to their strong relationship with the environment, and as a culture strive to live in harmony with the natural world. This balance has been jeopardized over the past century because of radical climate shifts in the region. Beyond the fringes of these remote communities, new challenges are being posed to states whose economic and societal health may be affected by climate change.

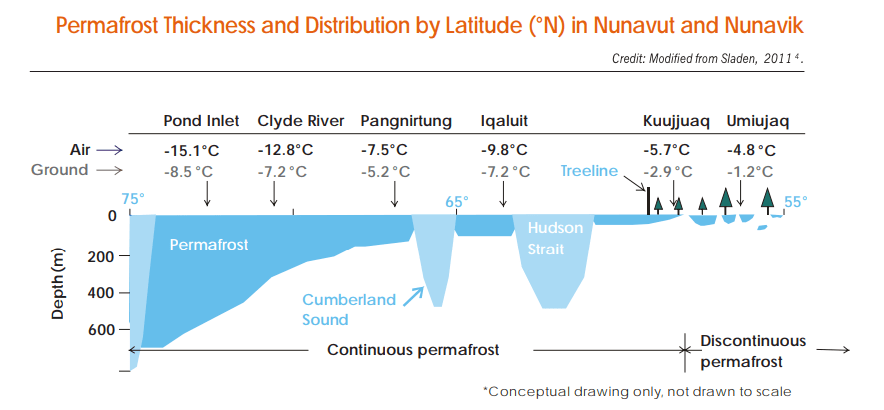

In Nunavut, mean temperatures widely vary depending on the area. Some areas rise to 30°C in the summer and in the winter range from – 15°C to – 40°C (Descamps et al, 2017). Most of Canada’s permafrost is found in Nunavut, as the ground is consistently at a temperature that can sustain it. Permafrost is important for two primary reasons; it sustains the ecological balance of flora and fauna that the Inuit rely on, and it contains massive methane stores in the ground which, if released, would further an already struggling ozone layer in the region. The Northern Canadian Arctic, specifically Nunavut, is facing significant threats to their periglacial environment that will burden the surrounding Inuit communities. The periglacial environment refers to the fringes of the permafrost landscape, areas in which the seasonal freezing and thawing offers areas for hunting and gathering. Permafrost is thawing at record rates. The influence of climate change has negatively impacted indigenous communities; precipitation patterns are altered, and bountiful vegetation and wildlife are becoming sparse.

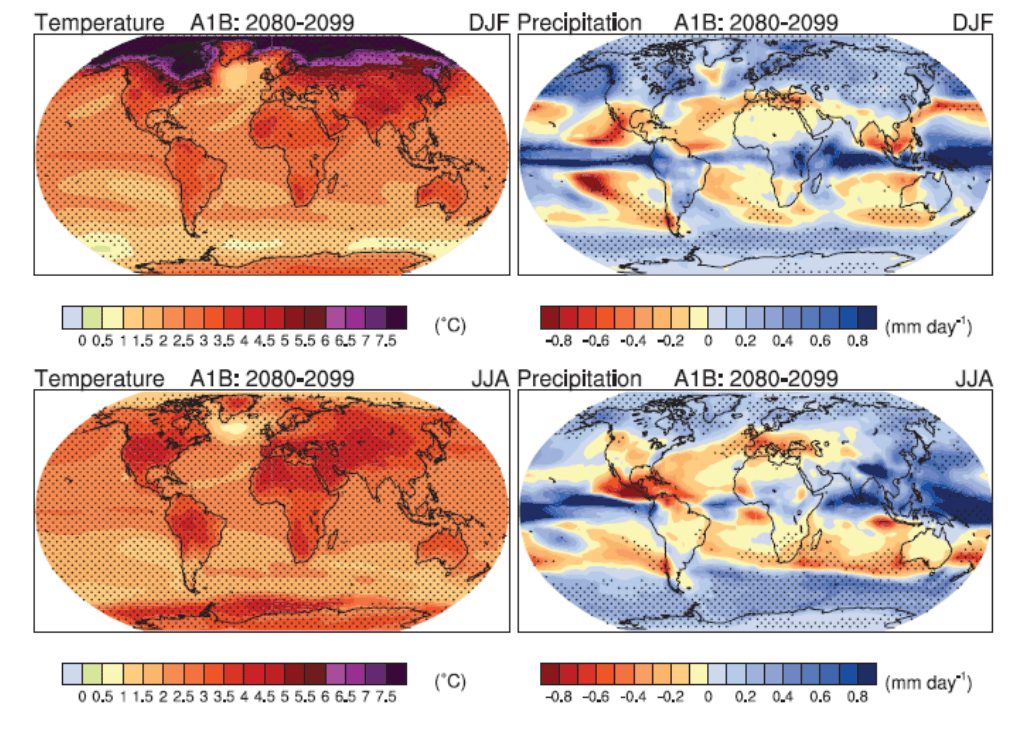

Following a century of data collection from 1950 to 2016, research indicates an average temperature increase of 2.7 degrees in Nunavut (Ford et al, 2014). This temperature rise has inflicted dramatic changes to Nunavut’s ecology. A Canadian study indicated that the rate of global warming is the highest in the northernmost territories with expedited extreme weathering and mass wasting events. Since early 1978, the Canadian Forces Station Alert in Nunavut has routinely measured ground temperatures up to depths of sixty meters (Pope et al, 2012). The observed patterns presented by the data collected indicate the significance of global warming to the dramatic changes in the Canadian arctic. This data indicated a general increase in air temperature of 0.12°C each year as well as an observed rise in permafrost temperatures increasing consistently by 0.15°C each year (Ford et al, 2014). The air temperature in the high Arctic is projected to increase at almost twice the global average.

The protection of permafrost is dire to Canada as its northern landscapes become increasingly relevant to resource extraction and Nunavut’s communities. As climate change is heavily influencing arctic ecosystems and hydrological systems, the thermal state of permafrost is dramatically changing. As permafrost thaws, it weakens the structure of the ground which promotes erosion and increases the depth of the active layer (Smith et al, 2021). The active layer is the section of earth that allows for nutrient transfer between the surface and the soil as it freezes and thaws. The increased depth leads to a change in absorption of water and nutrients, which results in the alteration of flow (Bosquet, 2010). The influence of climate change is fast-tracking permafrost thawing and impacts the stability of preexisting infrastructure and architecture in arctic communities such as main roadways, waste containment facilities, government buildings and hospitals. Several mining projects are proposed for Nunavut which may not be possible to execute due to the implications of permafrost thaw (Instanes, 2016). These warming conditions negatively impact Nunavut’s preparedness to engage in Canada’s economy.

Nunavut is experiencing sea ice loss at a dramatic rate. With the use of remote sensing technology, imagery, and classification, researchers have been able to accurately identify the rate of sea ice melt in the high Arctic. It was recorded that at the end of the “melt season” from 1953 to 2006, the average sea ice loss was -7.8% per decade (Descamps et al, 2017). The sea ice melt has increased rapidly per decade, at -12.4%, determined over the period of satellite measurements recorded from 1979–2010 (Glacier Monitoring and Assessment, 2020). In Nunavut, sea ice is not only a vital habitat for Arctic marine and wildlife, but it also plays a critical role in the daily lives of local Inuit populations. Reliant on local wildlife for survival, Inuit communities have noticed an absence of their essential hunting targets, specifically, walrus and seals. In Nunavut’s coastal region at the top of Baffin Island, fossils have been uncovered that indicate dramatic sea ice changes that point to the relocation of local marine life (Nuttall, 2007).

On land, permafrost disturbance and thaw negatively influence vegetation in Nunavut. Through rain-on-snow events, rain in the winter freezes and generates a thick ice barrier between uncovered bush and viable vegetation that provides nutrients for herbivores, making it more difficult to obtain nutrients (Ford et al, 2014). The alterations that climate change impedes on terrestrial ecosystems are irreversible and damaging to the surrounding wildlife and indigenous communities alike. Plentiful vegetation is equally important to the Inuit population, as these communities are heavily reliant on both wildlife and vegetation to survive. The formation of active layer detachment, also commonly referred to as ALDs, creates depressions on the landscapes that cause snow accumulation (Bosquet, 2010). ALDs, if triggered by permafrost instability, can result in slope failures due to ground ice melting which ruins surrounding vegetation (Bosquet, 2010). Thaw of permafrost will pose significant alterations to these conditions which will negatively impact tundra soil composition and therefore, influence plant and vegetation growth.

Climate change is a global issue, however, some areas of the world are impacted more than others. Inuit communities in the high Arctic will experience the extreme shortcomings of climate change in their own backyard before other areas and peoples. The steadily increasing air temperature orchestrated by climate change contributes to significant permafrost thaw, as soil becomes weaker due to permafrost thaw, local infrastructure is becoming unreliable. Sea ice loss coincides with vegetation and wildlife disruption which makes pursuing a hunter-gatherer lifestyle difficult for Inuit communities in Nunavut. Climate change is negatively influential and has imposed negative repercussions on Indigenous groups in Canada, specifically Inuit communities.

Figure One: Thermal map by the IPCC depicting changes in global air temperature and precipitation levels for boreal winter (top) and summer (bottom). Clear increases are predicted for the high Arctic, particularly in the winter months (Nuttall, 2007).

Figure Two: Chart depicting the thickness of permafrost based on Latitude distribution in Nunavut and Nunavik. By using clear symbology, the influence that permafrost thaw has on soil is evident (Bosquet, 2010).

Citations

Bosquet. (2010). The effects of observed and experimental climate change and permafrost disturbance on tundra vegetation in the western Canadian High Arctic

Descamps, S., Aars, J., Fuglei, E., Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., Pavlova, O., Pedersen, Å. Ø., Ravolainen, V., & Strøm, H. (2017). Climate change impacts on wildlife in a High Arctic archipelago – Svalbard, Norway. Global change biology, 23(2), 490–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13381

Glacier Monitoring and Assessment, Penny Ice Cap, Nunavut. Nunavut Climate Change Centre. (2020). https://climatechangenunavut.ca/en/project/glacier-monitoring-and-assessment-penny-ice-cap-nunavut.

Instanes, A. & Anisimov, O.. (2016). Climate Change and Arctic Infrastructure. Proceedings of the Ninth International Permafrost Conference. 1. 779-784.

Ford, J. D., Willox, A. C., Chatwood, S., Furgal, C., Harper, S., Mauro, I., & Pearce, T. (2014). Adapting to the effects of climate change on Inuit health. American journal of public health, 104 Suppl 3(Suppl 3), e9–e17. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301724

NASA. (n.d.). Penny Ice Cap in 1979 and 2000. NASA. from https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/9103/penny-ice-cap-in-1979-and-2000.

Nuttall, Mark. (2007). An Environment at Risk: Arctic Indigenous Peoples, Local Livelihoods and Climate Change. Arctic Alpine Ecosystems and People in a Changing Environment. 19-35. 10.1007/978-3-540-48514-8_2.

Pope, S., Copland, L., & Mueller, D. (2012) Loss of Multiyear Landfast Sea Ice from Yelverton Bay, Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada, Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 44:2, 210-221, DOI: 10.1657/1938-4246-44.2.210

Smith, S., Burgess, M. M., & Taylor, A. E. (2021). High Arctic Permafrost Observatory at Alert from https://www.arlis.org/docs/vol1/ICOP/55700698/Pdf/Chapter_188.pdf.

Leave a comment