Interpretations of Simulacrum

Sitting to watch a film is as common behaviour as any, there is little spectacle to this act, but at one point in the past it was quite the opposite. The moving images which now dominate our lives were once viewed with awe and wonder, not for the content depicted, but for the sheer fact that they could move. The first mass public screenings of films were in 1895 with the Lumiere brothers’ unveiling of the Cinematograph. At this first screening several short films, most ranging only a few minutes, depicted scenes as mundane as workers leaving a factory or men playing a game of cards. Attending this screening was Maxim Gorky, a Russian writer, who wrote an insightful reflection on the experience of viewing these films firsthand.

Gorky‘s observations on the Lumiere brothers’ first screening can explain how form and content may have been observed in early films. Contrasted to the oversaturated visual media culture of today, the spectators at the time would have seen much more depth to the form than we might observe. In films displayed at the Lumiere brothers screening such as; “Baby’s Breakfast’, “ The Arrival Of The Train”, and “The Gardener”, scenes of daily life in the late 1800s were projected onto a wall as a still until “suddenly a strange flicker passes through the screen and the picture stirs to life” 1.

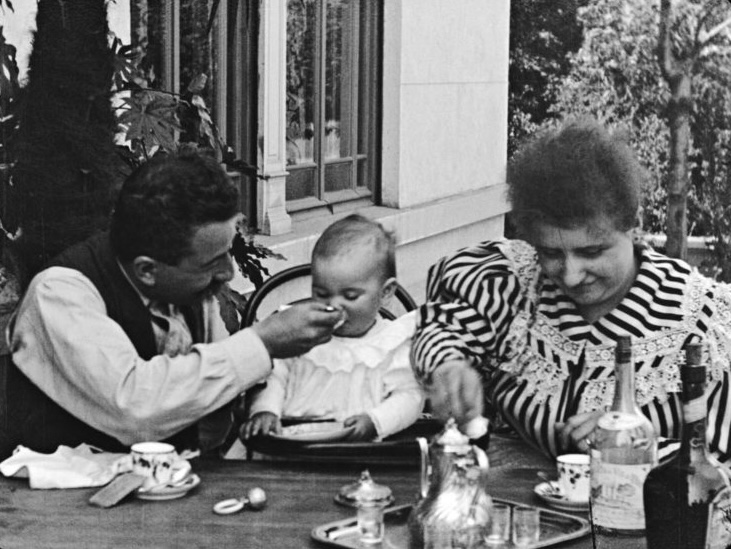

Still from ” L’Repas de bébé ” 1895 also known as “Baby’s Breakfast”

According to Gorky, “The extraordinary impression it creates is so unique and complex that I doubt my ability to describe it with all its nuances.”2 Upon viewing these films it might seem that there isn’t much to describe at all, let alone nuance. However, we have to curb our modern gaze to view these films if we hope to understand the complexities others saw at the time of their release. In “Baby’s Breakfast” the baby, about to take a bite of their breakfast, looks up and gestures beyond the frame of the camera to people outside the shot, “breaking the fiction of the event”3. The widely known notion that these films are considered the first documentary style films and the concept of “breaking the fourth wall” could render this moment trivial now. We know it is real life but with the addition of the camera, the event becomes a spectacle.

Moments we might consider a part of the mise-en-scene provided much to think about in these early films. A notable moment in “Baby’s Breakfast”, one often debated about , is the wind blowing through the leaves in the background of the shot. In an attempt to understand why this detail might have been so captivating, many speculations have been made. Poignantly put by Mary Ann Doene “Seeing the unplanned movement of the windswept leaves captured onscreen coincides with a uniquely modern paradigm in which chance, ephemerally, and spontaneity are newly privileged modes of experiencing the world.”4 Without intending it, the instance of wind blowing through trees represented the rich details of our lives that are often overlooked. For instance, the photograph is viewed as something created by the artist, carefully manufactured, and posed as a still, leaving little room for the spontaneity of nature’s whims in a painting or portrait. These mediums curated and froze still images exactly as they planned. Having a moving image allowed for outside influence to enter the frame.

Still from L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat 1895

Gorky’s profound insights come later in his writing; “This mute, gray life finally begins to disturb and depress you. It seems as though it carries a warning, fraught with a vague but sinister meaning that makes your heart grow faint. You are forgetting where you are. Strange imaginings invade your mind and your consciousness begins to wane and grow dim …”.5 Even in the first screenings of films Gorky examines the feeling of his “conciseness beginning to wane and grow dim”, a perception that is still relatable over a hundred years later. What is it about this act of observation that makes us feel this way? That it should carry such a severe warning to us even upon first viewing it.

Perhaps Gorky observed a cyclical nature to these short bursts of daily life, the actor, playing in their real life, stuck on repeat. The film becomes not a wonder of modern innovation but a feedback loop, the same on which we might see undesirable realities of life reflected at us while we watch TV or a film. The paralleling observations between the late 1890s and modern-day illuminate that, although when the novelty of film was fresh, it still managed to elicit a similar response in the public. Perhaps it isn’t the content of the films or the way they are shown, but rather the obfuscation of viewing people of the past carrying on life in repeat. Displaying both the illusion of magnificence and sombreness at the same time.

Sources

Form vs Content in Film, Explained. Accessed 24 February 2023. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=3HG8Q9ucr4k.

Gorky, Maxim. ‘LUMIERE’S CINEMATOGRAPH’, 4 July 1896. https://mes152bmcc.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/lumierescinematograph.pdf.

Jordan Schonig. ‘Contingent Motion: Rethinking the “Wind in the Trees” in Early Cinema and CGI’. Discourse 40, no. 1 (2018): 30. https://doi.org/10.13110/discourse.40.1.0030.

Leave a comment